If startups can do more with less capital thanks to AI and automation, what does this mean for the venture capital (VC) industry that funds them? The implications are profound. Traditionally, venture capital’s role has been to provide the significant funding needed for startups to scale (hiring, marketing, etc.) in exchange for equity. But in an environment where a startup might only need a few hundred thousand dollars – or no outside capital at all – to reach profitability or substantial revenue, the value proposition of traditional VC is challenged .

In an AI-enabled venture ecosystem, human and intellectual capital trump pure financial capital . That is, the best ideas and teams might not need as much money, but they might need other support (like AI resources, infrastructure, or networks). Venture capital firms, therefore, may have to evolve from being primarily money suppliers to being true value-add partners. Already, a few VCs try to differentiate by offering “platform” services (like recruiting help, PR, or strategic advice). But the new style venture building suggests a shift beyond that: VCs might need to white-label or even build actual venture-building platforms and AI tools to the startups that they back.

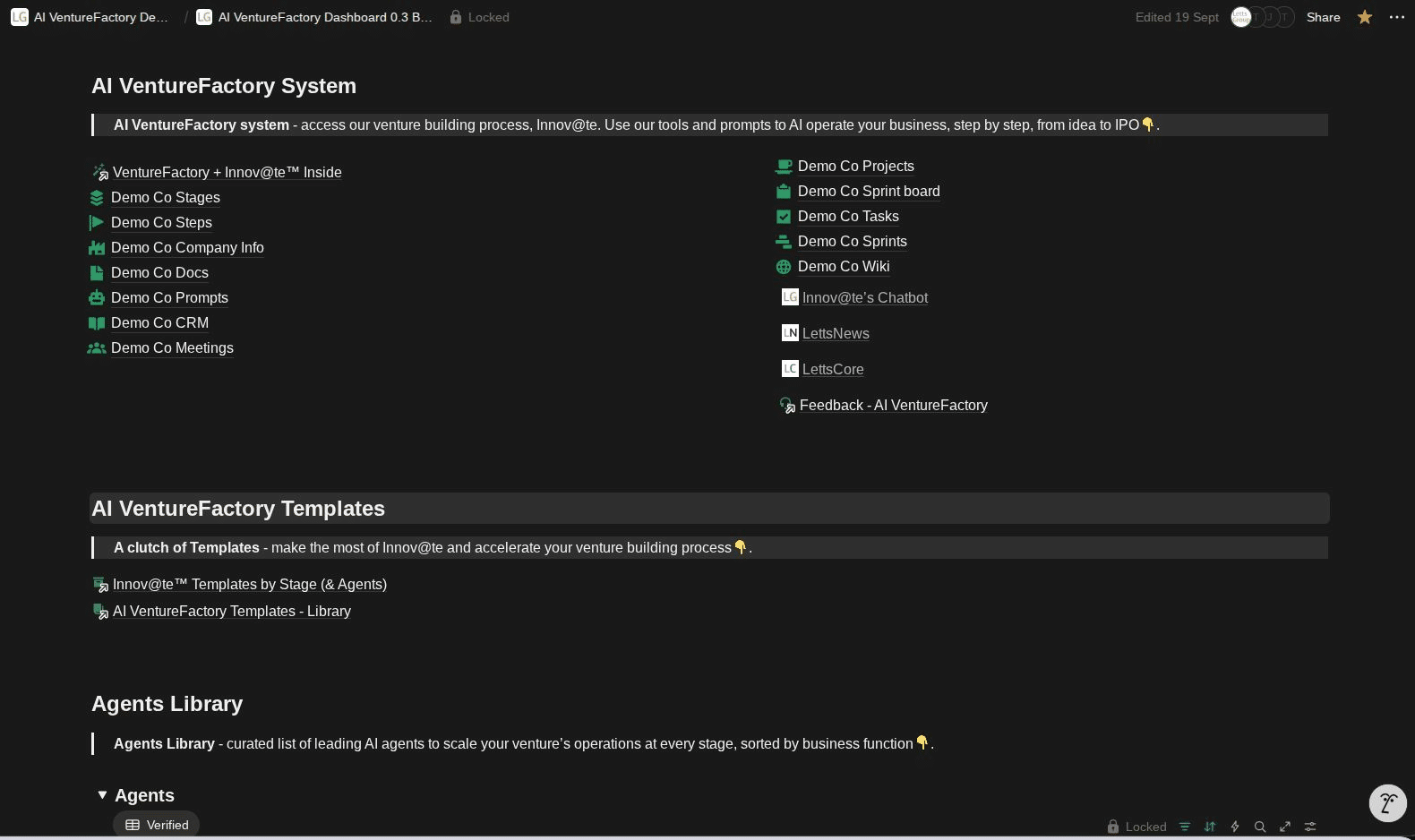

One likely outcome is the rise of “operational venture capital” models and venture studios run by investors . We have seen early steps of this with firms like a16z (Andreessen Horowitz) building large internal teams to help startups, or Project A in Europe which has functional experts on staff to deploy to portfolio companies. LettsGroup itself positions as a “new category of venture builder” that builds and sometimes even backs ventures through their AI VentureFactory, aiming for systematically better outcomes . And LettsGroup's new VentureFactory dashboard for VCs enables them to come to the table not just with a check, but with a platform like its AI VentureFactory that the startup can plug into for instant scale capability. Essentially, the VC firm itself could act more like a venture factory or incubator for its portfolio.

Another implication is on the financial side: smaller rounds and potentially leaner valuations in early stages. If a startup can get further on its own or with less money, it may delay raising or raise less. This could mean fewer equity dilutions for founders and a harder time for VCs to deploy large funds. Some VCs might respond by focusing on quality over quantity and earlier stage deals – investing in more startups with smaller tickets, hoping that higher success rates (even if exits are smaller on average) will yield good returns. The old model of needing a few unicorns to pay for all the duds might shift if there simply are fewer duds (because venture building is more predictable). In such a scenario, VC portfolio strategy could become a bit more like private equity – targeting solid businesses and helping them grow efficiently – rather than a high-risk lottery.

However, one could also argue that easier scalability will create bigger successes too, not just moderate ones. A startup that grows super efficiently might capture markets faster and end up a huge win with minimal capital. That’s great for founders, but for VCs it raises the question: how to ensure you’re part of that journey if your money wasn’t needed early on? This is where disintermediation risk comes in. If founders don’t need as much VC money, they might skip it or use alternative financing (like revenue-based financing, crowdsourcing, corporate investors, or grants). Moreover, AI itself could connect founders directly with capital sources. One analysis predicts that AI agents will link entrepreneurs to investors directly, potentially bypassing traditional VC firms . We can imagine AI-driven platforms (perhaps blockchain-based or marketplaces) where startups get matched with interested investors (angel, family office, etc.) without going through the classic VC gatekeepers. If that becomes common, the power of big VC funds could diminish, unless they partake in those platforms.

VCs are aware of these shifts. In fact, some forward-looking venture firms are already experimenting with automation internally – for example, using AI to screen business plans or perform due diligence faster. But those are incremental improvements to their operations. The larger disruption is if the venture firms themselves must change their model . The LettsGroup vision hints that “the venture capital firm of tomorrow will function as an AI system with an associated network of entrepreneurs.” In practice, this could look like a VC that has built or white-labelled its own AI venture factory (like a LettsGroup for external ventures) where it can spin up companies almost on demand, assigning great entrepreneurs to lead them, with all the back-end provided. Such a firm might not evaluate deals in the traditional sense; rather, it co-creates ventures, providing both the idea or platform and the funding. This blurs the line between investor and builder. It’s almost a venture builder-VC hybrid .

Another scenario is venture capital as a platform service that external startups subscribe to. LettsGroup literally states they are on a mission to build and enable “venture capital-as-a-platform”. They have kicked this off by providing their VentureFactory platform to other investors and corporate incubators or investors. In the future, a startup might pay for access to a VC’s platform (including capital, but also tools and guidance) rather than just taking a check. The VC would monetize not only through equity but possibly through subscription or profit-sharing models. This changes the revenue model of venture investing from purely equity returns to a mix of equity and service revenue. It could also democratise access – a startup that doesn’t get a term sheet might still be able to pay to use the VC’s platform/tools to improve and eventually earn investment.

For traditional venture capitalists, these changes pose a challenge: how do you stay relevant when capital is commoditised? The likely answer is they must move up the value chain – offer things that money alone can’t. This might include:

We might also see a shift in power towards founders . If one of the aims of AI venture building is to empower entrepreneurs (and indeed some argue the AI-enabled future should “ultimately empower entrepreneurs more effectively than simply enriching venture capitalists”), then founders with good track records or strong ideas will have more options. They could choose to go it alone longer, or demand better terms from investors. The balance of negotiation could tilt slightly towards founders who have an AI-boosted operation and are less desperate for cash. This might result in friendlier deal terms, less onerous preferences, etc., as VCs compete to get into good deals. We’re already seeing super large funds and many new funds chasing a finite set of great startups; if those startups need less funding, the dynamic intensifies.

Interestingly, some new venture entities like Steel Perlot (backed by Eric Schmidt) are positioning themselves in line with these trends. Steel Perlot aims to “identify, invest in, and develop multi-generational platforms” and sometimes builds companies directly, only supporting those they think can reach global scale. This is a more interventionist model of venture investing , focusing on systemic change in target industries and blending capital with deep involvement. It aligns with the idea that VCs will pick specific domains to specialise in with technology (Steel Perlot presumably leverages AI expertise from its backers) and ensure their ventures in those domains benefit from that infrastructure.

We also see corporates entering the venture building space (corporate venture studios or incubators) which could become competitors or partners to VCs in funding innovation. If corporations build new companies internally using venture factory methods (like Mach49’s work with large firms), they might spin them out or fund them in ways that bypass traditional VC rounds. VCs might then find fewer high-quality independent startups, as some are birthed and grown inside corporate ecosystems or by venture platforms.

To adapt, venture capital might look more like “innovation capital” integrated with incubation . For example, a fund might say: “We invest $500k and also enroll you in a venture building platform which will handle X, Y, Z for your company.” The success metric might shift from just financial returns to also the success rate of portfolio (bragging about how 60-70% of their startups hit profitability, for example, rather than 90% failing). If investors can claim that their involvement doubles a startup’s chance of success, that’s a powerful selling point to founders deciding whose term sheet to accept.

There’s also the possibility that VC as we know it fragments into new forms:

Finally, the economics for VCs might shift. If startups require less money overall, funds might either shrink in size or find new ways to deploy capital (maybe investing in more startups or returning money to LPs sooner). The high management fees of mega-funds might be harder to justify if one can’t invest that money well due to more efficient startups. Conversely, if venture factories dramatically increase the number of viable startups, there could actually be more companies to invest in (just each needs less), potentially broadening the market for early-stage investing.

In summary, the implications for venture capital include:

As one Letts Journal article concluded, “tomorrow’s entrepreneurs may integrate with venture factory platforms rather than traditional legal structures that offer limited value beyond capital” , shifting greater control and value creation to founders and innovative builders. Venture capital firms, to remain central, will likely transform into these very platforms or align with them. We are likely to witness a convergence of roles: investors becoming builders and builders becoming investors – all facilitated by AI and systematic processes. The venture capital industry has always been about taking calculated risks on innovation; now it may have to innovate its own model to keep up with the entrepreneurs who increasingly can flourish without it.

The next section of our guide to New Style Venture Building is 'Founder Mode vs. Manager Mode Leadership' - coming soon.

If you are a founder or investor, sign up to LettsGroup's AI VentureFactory today.