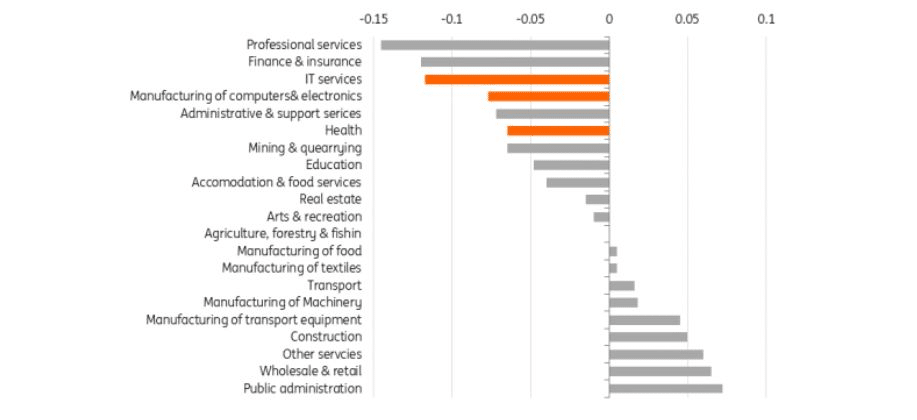

The European Union finds itself in a paradoxical position. The region accounts for 19% of global R&D investment, produces 20% of global scientific publications, and houses 43% of the world's leading life sciences universities. Yet as an ING analysis reveals, from 2000-2019, productivity growth in Europe's high-tech sectors lagged significantly behind the US, with a negative gap of approximately 0.1 percentage points annually in manufacturing of computers and electronics.

This productivity chasm has profound consequences. While high-tech manufacturing has increased production by an impressive 60% over the past decade, competing sectors in the US have grown faster, widening the transatlantic technology gap. The stark reality, as detailed in the Draghi report, is that Europe's most innovative sectors remain caught in what economists term a "middle technology trap", excelling at incremental improvements while failing to pioneer breakthrough innovations that create market-defining platforms.

"The road ahead is not without challenges," notes Lukas Leitner, a deep tech investor at Lakestar. "The U.S. has a 'flywheel effect' in deep tech while Europe's ecosystem is still immature."

At the heart of Europe's tech leadership deficit lies a profound cultural distinction: risk aversion. As Bloomberg columnist Allison Schrager observes in a recent Japan Times piece, "European culture is just more risk-averse than America's. There is a reason stock ownership is lower and welfare states are bigger in Europe."

This risk aversion manifests in multiple dimensions:

This cultural orientation toward security over opportunity creates a systemic handicap for European tech development. As Leitner observes, "Europe has strong research institutions, engineering talent, and supportive public sentiment for deep tech, but there need to be policy changes to foster a culture that supports taking risks."

Perhaps most critically, Europe suffers from a pronounced leadership gap in its tech ecosystem. While the US has produced daring tech leaders like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg - figures willing to pursue massively ambitious, high-risk ventures - Europe has generated comparatively few equivalent entrepreneurial icons.

This leadership deficit has several dimensions:

The leadership gap creates a vicious cycle. Without visible examples of audacious tech leaders achieving massive success, the next generation of European entrepreneurs calibrates their ambitions and risk appetites accordingly, perpetuating the pattern of more modest ventures.

Europe's venture capital landscape, while growing, remains fundamentally different from its American counterpart. According to data cited in the ING report, venture capital as a percentage of GDP in the EU is approximately one-fifth of US levels. More troubling, the concentration of late-stage funding is even more pronounced, with European tech companies raising on average just half the capital of their American counterparts at equivalent funding stages.

The funding gap results in a systematic disadvantage for European startups. A recent TechCrunch piece reveals that 50% of the growth capital raised by European deep tech startups comes from outside the continent. The finance issue isn't merely quantitative - it's structural. The EU has been bluntly criticised for a financial infrastructure that is not in place, a struggling market for investing in tech; all ultimately increasing its risk aversion compared to the US.

Europe faces an alarming talent deficit. A Euractiv Advocacy Lab piece documents that against EU targets of 20 million ICT specialists by 2030, current projections suggest only 12 million skilled professionals may be available. This 8-million-person gap represents perhaps the single largest constraint on Europe's digital ambitions.

While Europe has increased its AI professional base tenfold over the past decade, China leads in sheer numbers of AI practitioners. The World Economic Forum forecasts that 70% of the next decade's economic value will stem from digitalisation, making this skills shortage potentially devastating to Europe's competitive position.

Despite decades of integration efforts, Europe's digital landscape remains fragmented. As the ING analysis states, "Cross-border consolidation for economies of scale has proven more difficult in Europe due to fragmented and stricter regulation and competition policies for consumer protection."

This fragmentation creates profound scaling disadvantages. European tech companies must navigate 27 different regulatory regimes, language markets, and consumer preferences - diluting resources and complicating growth strategies. By contrast, American tech companies can achieve massive scale in a single, homogeneous market before approaching international expansion.

Perhaps most alarmingly, Europe has developed critical dependencies on foreign technologies in infrastructure domains. In a 'The Rest is Politics' question time podcast, Campbell and Stewart identify cloud computing as "entirely American" and notes Europe's reliance on US companies for defence resources marked by US-owned data gathering mechanisms.

These dependencies extend into security domains, with specific mention of companies like "SpaceX and Palantir" representing areas where Europe lacks sovereign alternatives. The podcast suggests that the EU is completely reliant on US tech.

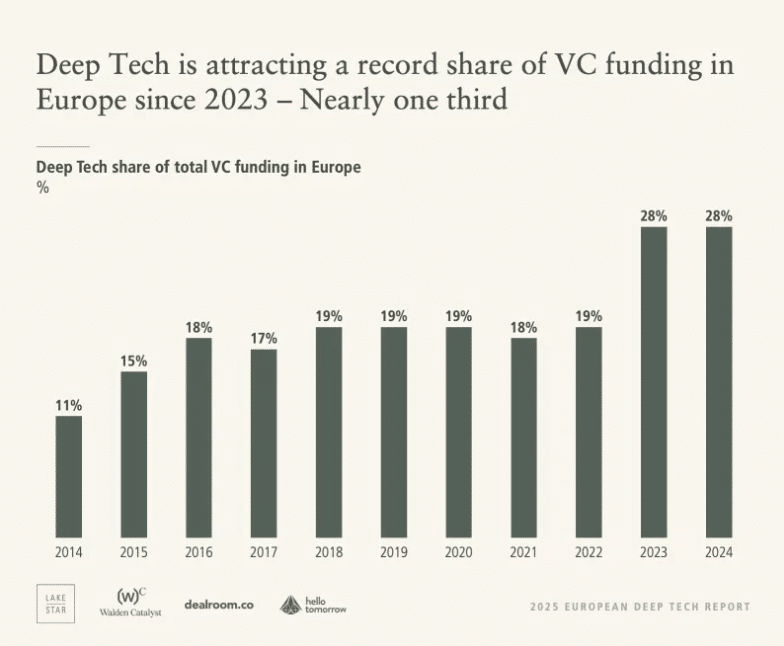

Against this challenging backdrop, deep tech may represent Europe's most promising path toward technological sovereignty. According to a 184-page report by venture firms Lakestar, Walden Catalyst, Dealroom, and Hello Tomorrow, deep tech attracted €15 billion ($16.3 billion) in venture investments in Europe in 2024, with nearly one-third of all European venture capital now directed toward deep tech companies.

European strengths in deep tech are substantial:

As Arnaud de la Tour, CEO of Hello Tomorrow, notes: "The National Science Foundation, which is the biggest supporter of founder-applied research in the U.S. has had its budget cut by half. A lot of those great scientists don't have a job anymore, and many could come to Europe."

Alongside the deep tech opportunity, innovative approaches to venture creation deserve careful examination. LettsGroup's AI VentureFactory represents one of the most systematic attempts to address Europe's venture-building challenges. The company's approach is based on a fundamental insight: the traditional venture-building process remains remarkably artisanal despite technology transforming nearly every other industry.

LettsGroup has developed what it calls the Innov@te methodology - a comprehensive venture-building framework with seven stages, 49 distinct steps, and hundreds of sub-steps developed over 15 years. This approach transforms what has historically been tacit, founder-dependent knowledge into explicit, transferable systems, potentially offering a solution Europe's crippling risk-averse landscape.

The potential impact is significant. LettsGroup claims its systematic approach can double conventional venture success rates from one successful venture in ten to one in five. If accurate, this would represent a dramatic improvement in capital efficiency - a critical advantage in Europe's more constrained funding environment. The AI VentureFactory also claims it's approach can reduce the cost of venture building by up to 90%.

The AI VentureFactory addresses several European structural challenges:

What makes this approach particularly relevant to Europe's challenges is its systematic nature. Rather than attempting to copy Silicon Valley's high-risk, founder-genius model, LettsGroup has created a structured methodology and AI-powered software platform that potentially fits better with Europe's more process-oriented business culture while still delivering improved outcomes.

For Europe to create genuine tech leaders capable of ensuring digital sovereignty, four essential transformations must occur:

Europe must undertake the difficult but necessary cultural shift toward embracing calculated risk-taking in technology ventures. This doesn't mean abandoning European values of stability and security, but rather recognising, as Schrager puts it, that "technology-driven growth is inherently unpredictable and creates winners and losers."

This shift requires several elements:

The LettsGroup model potentially offers a bridge by creating more systematic approaches to risk management without reducing the inherently risky nature of technological innovation.

The evidence is clear: Europe's capital markets must undergo fundamental transformation. As the ING report states, "European capital markets, fragmented and risk-averse, fail to provide the financing needed for global competitiveness."

This transformation would require regulatory changes to facilitate cross-border investment, institutional shifts in risk appetite, and dedicated mechanisms to bridge the "valley of death" between early-stage funding and growth capital.

Addressing the 8-million-person ICT skills gap requires a comprehensive strategy across education, immigration, and remote work policies. The Euractiv piece highlights one small-scale initiative - Huawei's partnership with UNESCO on ICT competitions - but systemic solutions demand coordinated action at the European level.

Universities must expand technical programs, mid-career retraining initiatives need significant scaling, and Europe must develop compelling value propositions to retain and attract global tech talent.

Europe cannot achieve technological sovereignty across all domains simultaneously.

Such focus might concentrate on deep tech areas where Europe has natural advantages, like photonics computing, which offers "major advantages in speed and efficiency" according to Leitner. By leveraging specific domains of excellence, Europe could develop distinctive technological capabilities that provide strategic independence.

Can Europe create genuine tech leaders capable of ensuring digital sovereignty? The evidence suggests qualified optimism, but only if Europe embraces transformative approaches rather than incremental adjustments.

The deep tech sector's growth, now attracting nearly a third of all European venture capital, indicates investors recognise this potential path to technological sovereignty. Meanwhile, the AI VentureFactory approach developed by LettsGroup offers a systematic methodology that could help Europe maximise returns from its more limited capital resources while addressing the risk aversion challenge.

The current geopolitical environment may also create unexpected opportunities. As de la Tour notes, science defunding in the US could drive talent toward Europe, while photonics computing represents a domain where Europe can lead rather than follow.

As Schrager concludes in her analysis of European risk aversion, "finding the right balance between reducing risk and encouraging growth is as much about values as about economics." Europe possesses the fundamental assets needed for tech leadership: world-class research, substantial financial resources, regulatory sophistication, and democratic legitimacy. What it has historically lacked is the cultural comfort with risk, the leadership examples, and the institutional coordination necessary to translate these assets into global tech leadership positions.

By combining deep tech investment with systematic venture-building methodologies like LettsGroup's AI VentureFactory, while simultaneously undertaking the harder cultural shift toward embracing smart risk-taking and developing more risk-tolerant leaders, Europe might just find its path to genuine technological sovereignty. The stakes couldn't be higher, particularly in the "Trumpocene" era where, as William Burns argues, "Europe urgently needs to rethink technological sovereignty."